As has been clearly shown during the COVID-19 pandemic, RNA vaccines are an incredibly powerful tool. We have seen how potent they are against a rapidly emerging infection, with the speed at which they can be produced a major benefit. From the first genome sequence published to the first experimental vaccine dose designed, manufactured and administered was seventy-one days, less time than it takes to make cheese. However, more work is needed to deliver on the promising start that RNA vaccines have had.

One of the challenges has been with the side effects of the vaccine, sometimes called reactogenicity. This is in part caused by the body’s reaction to the vaccine itself: RNA is a trigger for immune reactions, it is how the body sees viral infections. Tweaking the amount of RNA in the vaccine, whilst maintaining its ability to induce a protective antibody response is one way in which we can improve RNA vaccines.

We have been interested in a slightly different approach, called self-amplifying vaccines. We showed (pre-pandemic) that these saRNA vaccines can lead to protection for a much lower dose. These vaccines are based on RNA, but able to make more copies of themselves in the injected muscle, giving you more bang for your buck. Professor Robin Shattock (also at Imperial College London) performed the first in human clinical study using saRNA vaccines during the pandemic. This trial had a mixed result, with not all of the volunteers producing antibodies after vaccination. In parallel with this first in human study, we looked at how the vaccine might work in other model organisms, as a way to understand how these vaccines work.

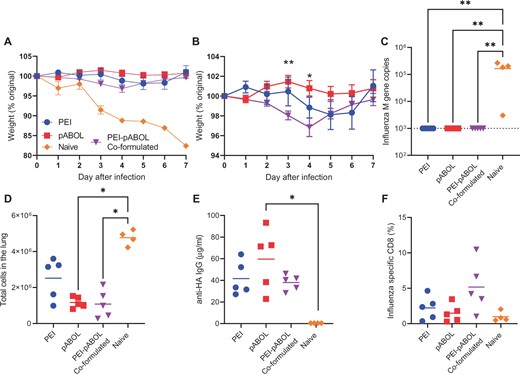

In our recent study Polymer Formulated Self-Amplifying RNA Vaccine is Partially Protective against Influenza Virus Infection in Ferrets, we tested the immune response to saRNA vaccines in ferrets. This might sound like an odd choice, but ferrets have a number of similarities to humans in they way they respond to infections, especially influenza. We set out to test whether saRNA vaccines could protect ferrets against flu. As with the human study, we had mixed results. The ferrets that responded to the vaccine by making antibody were well protected against infection, however, not all of the ferrets made antibodies. Understanding why this is the case is important in the future development of this extremely promising vaccine platform.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in